The centennial era of the Bolshevik Revolution heralded the return of the “Russian question” back to the center of American political debate, where it certainly looks set to remain. In 2021, for example, the Biden Administration declared Russia and China the greatest threats facing the US-led world order just before Russian President Putin launched his war of choice upon Ukraine, with China his most formidable ally. However, while the latter has long been portrayed as a relatively fixed sociopolitical antipode to the West, Russia’s distinctive “otherness” from Europe and North America has posed a far more mutable conundrum since well before the first Cold War. What’s more, despite the vast scholarship on Russia’s relations via-a-vis the West, most analyses avoid more than a cursory discussion of the racializing logics behind such assertions of difference, if they engage the topic at all. My book project, America’s Russia: The Bolshevik Revolution, US Print Culture, and the Concept of Eurasia, 1881-1929, argues these mercurial links between Russia, the West, and Asia underscore a largely ignored historical current of the twentieth century at the intersections of racial formation and radical politics, which can be illuminated in part by centering the emergence, subsequent transnational circulations, and multiform durable effects of the discourses of Eurasianism within Russian-American cultural relations from the late nineteenth century to the Great Depression.

At the center of this ideological history, then, is the usefully malleable philosophy of Eurasianism itself. Inaugurated in the early 1920s largely by non-radical Russians fleeing their homeland in the wake of the Bolshevik ascent, Eurasianism was above all an attempt to explain what its adherents saw as Russia’s singular place in the world due to its sociocultural position at the interstices between Europe and Asia. As Marlène Laruelle explains, “born in the context of a crisis,” Eurasianism “continued the Russian intelligentsia’s long tradition of thinking about Russian otherness and its relationship to Europe.”[1] Combining nineteenth-century Slavophilia—a movement asserting that Russia develop on its own terms rather than mimic the West—with the historical rupture provided by the Bolshevik Revolution, Eurasianism became a usefully fluid “theory of nation and ethnos” that fostered “an assertion of the cultural unity and common historical destiny of Russians and non-Russian peoples of… parts of Asia.”[2]

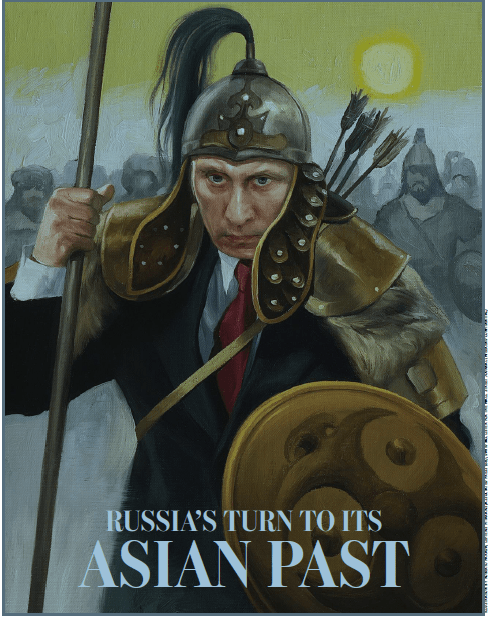

However, a sense of the “Eurasianness” of Russia existed well before the ideology was formally announced. Consequently, one focus of America’s Russia is the essential but largely neglected history of the racialization of Russians themselves. Perhaps surprising for today’s readers, the precise “race” of Russians for much of modern European history provided a profound challenge to emerging Western racial codes, and not only by outsiders. In the words of Leon Trotsky, “Russia stood not only geographically, but also socially and historically, between Europe and Asia. She was marked off by the European West, but also from the Asiatic East, approaching at different periods and in different features now one, now the other.”[3] Or, as Stalin more succinctly said to a visiting Japanese journalist in 1925, “I too am Asian.”[4] This liminality “between Europe and Asia”— what Larry Wolff has called the region’s “demi-Orientalization”—allowed the variability of Russia’s “race” to become politically expedient as well.[5] So if Russia during the nineteenth century was seen as a nation slowly en route to Western racial and political inclusion—an “East European country which happened to extend into Asia”—after Red October it once again became “an Asiatic country which extended ominously into Europe.”[6] With Russia’s revolution soon to be invoked in the service of both antiradicalism and racial nativism at once around the world, America’s Russia is also focused on how circulations of Eurasianist discourse were received and reworked by US-based writers of all stripes to strengthen their own agendas by conflating sociopolitical programs with racializing procedures and vice versa.

The historical and transnational scope of the project is organized through an introduction that maps the rise of Russia as a liminal site in the Western racial imaginary while also outlining the prehistories of what would become known as Eurasianism. This places the philosophy within the European intellectual tradition to illustrate the ways in which its emergence was in part a reappropriation of racial formations already assigned to Russia and, therefore, developed in some measure “under Western eyes.” I then chart the development of Russian-American relations mostly across the long nineteenth century, beginning in 1763 with the first “American” trading vessel docking in Russia, and continuing with other signal moments of engagement, such as the countries’ relatively contemporaneous emancipations of unfree subjects (the czar’s “liberation” of the serfs in 1861 conjoined with the formal abolition of American chattel slavery in 1865) and the sale of Alaskan “Russian America” to the US in 1867. I also engage a robust archive of travel writing from an ideologically and geographically disparate set of authors who nevertheless found strong similarities between the two nations. In the prophetic words of Alexis de Toqueville over a century before the Cold War: “There are today two great peoples on earth, who, though they started from different points, seem to be advancing toward the same goal: the Russians and the Anglo-Americans….Their points of departure are different, their ways diverse. Yet each seems called by a secret design of Providence someday to sway the destinies of half the globe.”[7]

Chapter one explores the life and work of American writer and explorer George Kennan to demonstrate how, beginning in 1882, his extensive writing on the Siberian exile system and single-minded focus on what he viewed as the “Oriental despotism” of the czar, was most responsible for defining modern Russia to legions of US readers for over three decades. Indeed, Kennan’s lectures and articles were so popularly reported and reprinted that, as two newspapermen from the time observed, Russia moved rapidly from infrequent curiosity to “one of the chief objects now before the public gaze” and “for most people in the United States, the gospel according to Kennan has become the truth about Russia.”[8]

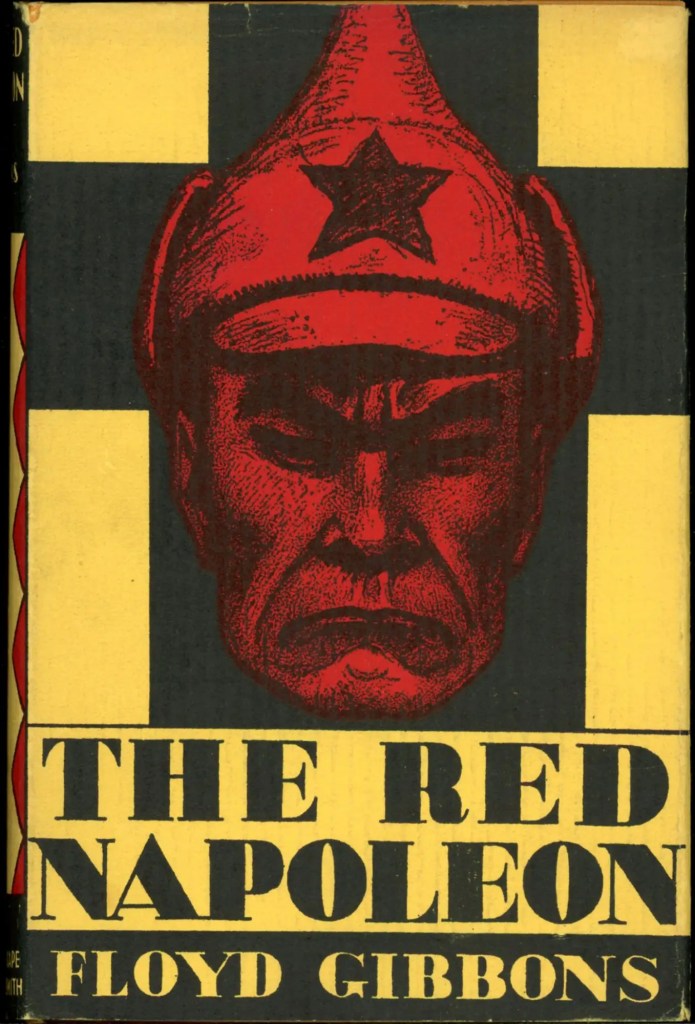

Chapter two begins with Sax Rohmer, creator in 1912 of one of the most enduring Orientalist characters in literary history, Dr. Fu Manchu—described in his first appearance as “the Yellow Peril incarnate in one man.”[9] This racist discourse, constructed in part upon medieval fears of Mongol invasions, “combines racist terror of alien cultures, sexual anxieties, and the belief that the West will be overpowered and enveloped by the irresistible, dark, occult forces of the East.”[10] With a particular focus on the serial distribution of the Fu-Manchu series across decades and continents, I outline how this character promoted a particularly threatening vision of Asia that was soon conjoined with fears of the Eurasian “Bolshevik menace.” I then turn to Jack London, the most popular socialist writer in the history of the US, through the same prism of Yellow Peril discourse to show how such delimiting dogmas were not lurking in the writings of racist reactionaries alone. London’s extensive coverage of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, (considered the first modern defeat of a European power by an Asian nation) and racialized fictions such as “The Coming Invasion” are contextualized through the only manuscript he ever left unfinished, a 1916 novella focusing on a Russian anticapitalist hitman to argue that his textual abandonment was due to a contradictory vision of socialism as both liberatory and a white racial project irreconcilable with his “Orientalized” Russian protagonist.

Chapter three shows how this new racial-political American “common sense” around Russia became distributed and normalized within US print cultures through the concept and cultural work of seriality, operating here as both method of distribution and theory of ideological production. Through a vast archive of textual materials—articles, editorials, serialized fictions, even advertisements—published between 1886 and 1924 by the Saturday Evening Post, the most popular magazine in US history, I catalog the transformation of the figure of the agitator from a hodgepodge of various immigrant and parlor radicals into a violent “Oriental” Bolshevik far more dangerous for its ability to racially “pass” beyond the more common American binary of black and white. As a Post editorial from 1920 frames the issue, the “average American” can “…see the negro problem; but they cannot grasp the Russian problem” though “sooner or later everyone must line up on one side or the other and take an active part in deciding whether this country shall remain America or become Russia.”[11]

Chapter four examines the works of immigrant Jewish, East, and South Asian writers living in the US to outline the “Orientalized” links between antisemitism and Asian exclusion. By comparatively examining the ways in which writers such as Abraham Cahan, Rose Pastor Stokes, Sen Katayama, and M. N. Roy understood their various American marginalizations, we can better apprehend how such differential experiences influenced their respective politics, their grasp of their own racializations, and their relationships with both the Bolsheviks and the US.

Chapter five maps the circulation of Black militants and their writings in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution. In magazines such as the Messenger, the Crisis, and the Crusader, I focus particularly on Black women activists like Grace Campbell, Louise Thompson Patterson, and Claudia Jones, who were inspired by Red Russia while also recognizing some of its programmatic limits at the confluence of racial, class, and gender analysis, leading them to formulate an “intersectional” approach well before the term in the service of freedoms for all.

In 2018, the Wall Street Journal attempted to dismiss Putin’s machinations with the headline “Russia’s Turn to Its Asian Past,” complete with illustration of the Russian president on horseback and clad in Mongol battle attire. While my project is not at all an attempt to exculpate Russia’s cynical and violent kleptocracy, it is in part a desire to understand how racialized ideologies like this continue to masquerade as analysis. If fortunate enough to receive such generous funding from the ACLS, I will complete the manuscript and submit the project to NYU Press after being encouraged to do so by their editor-in-chief earlier this year. During our contemporary moment of increased white supremacist nativism along with augmented movements for racial and economic justice and fears of a rising Asia conjoined with Russian influence, I hope to contribute at least a partial answer as to why Russia continues to “color” the US political imagination at the intersections of racial formation and radical politics today.

[1] Marlène Laruelle, Russian Eurasianism: An Ideology of Empire, trans. Mischa Gabowitsch (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2008), 476.

[2]Ibid., 221, 203.

[3] Leon Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution, trans Max Eastman. (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2008), 4.

[4] Hiroaki Kuromiya, Stalin, Japan, and the Struggle for Supremacy over China, 1894–1945 (London: Routledge, 2023), 84.

[5] Larry Wolff, Inventing Eastern Europe: The Map of Civilization on the Mind of the Enlightenment (Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 1994),

[6] George Lichtheim, Marxism, an Historical and Critical Study (New York: Columbia UP, 1982), 358; Martin Malia, Russia Under Western Eyes: From the Bronze Horseman to the Lenin Mausoleum (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1999), 292.

[7] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Library of America, 2004), 476.

[8] “Russian Traits and Terrors,” Public Opinion, (September 26, 1891), 618; Milwaukee Sentinel editorial, March 13,1892, reprinted in Public Opinion (March 19, 1892), 598.

[9] Rohmer, Sax. The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu (London: Methuen, 1913), 23.

[10] Gina Marchetti, Romance and the Yellow Peril: Race, Sex, and Discursive Strategies in Hollywood Fiction (Berkeley, CA: UC Press, 1993), 2.

[11]“Self-Preservation.” Saturday Evening Post, Feb. 7, 1920, 28.This book project is a study of the durable cultural effects that cohered in the US through its relationship with the nascent Soviet Union at the intersections of racial formation and radical politics. Specifically, this project examines the linkages between, among, and within entangled aspects of difference, such as race, class, gender, and sexual orientation, through the prism of the Bolshevik Revolution as represented within the periodical press.